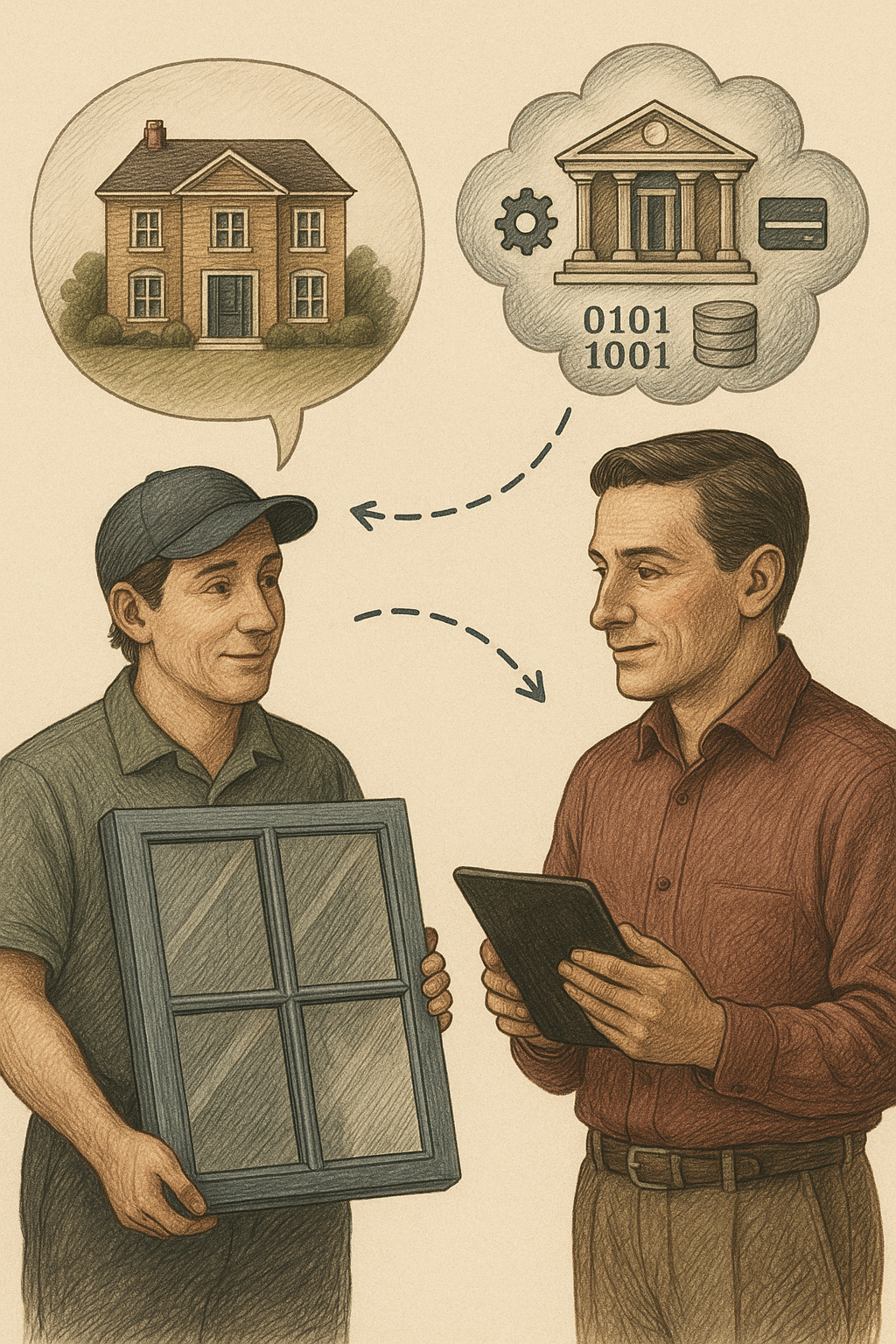

The ultimate goal of financial plumbing is to enable commerce in the real economy. Consider the humble window: it is a fairly expensive, surprisingly high-tech manufactured good, installed by the dozen in homes by artisans. A window represents a supply chain, and one part of that supply chain is a sales process, convincing a homeowner of the desirability of updating their windows. The sales representative running that process would urgently prefer to leave their single visit to the home with not just tentative measurements but with a durable commitment to buying the window and financing firmly in place for it.

Why finance the purchase? Windows cost $1,000 to $3,000 each and updating all or a large fraction of them quickly becomes a mid-five figures project; relatively few homeowners will pay upfront with cash. Moreover, the sales process would strongly prefer the purchase be financeable, because that will sell more windows than a counterfactual world where windows were only available for cash.

One could imagine a world in which window manufacturers or installers provided financing off of their own balance sheets. This would be a rough world for them: they have upfront capital outlay (the window) and would recoup only after extended periods, bearing credit risk all the while. No, they would prefer to sell windows for money. It’s frequently delivered in milestone payments, perhaps half prior to manufacturing the windows and half upon successful installation.

You could imagine the buyer could bring their own financing, perhaps by going to their usual bank and asking for a home improvement loan. That product very much exists, but it might be surprisingly less attractive to all parties: it will be costly, low margin for the bank, and have poor operational dynamics for the window company. And so you could imagine the window company asking the financial industry to come up with an alternative.

That alternative exists, and can underwrite and paperwork a four-party commercial loan in fifteen minutes, before the salesman has even left their home visit that sold the window. We’ll return to it in a moment.

Why not just have banks loan money for home improvement?

Again, very many banks do actually make home improvement loans available. But they’re not wonderful loans for the banks.

We’ll begin with the somewhat awkward dollar amount: a home improvement loan is enough money to hurt if it goes bad, but not enough money to justify a high-volume well-oiled machine to underwrite, not like e.g. mortgages. And indeed that is what many banks will immediately try to sell you if you ask for a loan for the purpose of home improvement: can we instead counterpropose a home equity line of credit (HELOC)? You can then borrow against your existing home equity, withdrawing cash, and we have no objection to you swapping cash for a window, a decision we need hear no more about. We have a supply chain for mortgages, including HELOCs, and this supply chain will decrease our capital requirements while smoothing every part of underwriting.

Why does the bank want to take the window out of the window purchase? Because a home improvement loan otherwise requires multiple operationally intensive document reviews and conversations where bankers talk to construction company office managers. Those conversations are frequently unhappy ones.

Consider the case where a construction project flies off the rails, which has been known to happen. The window company says it has installed the windows, and potentially they have a certificate proving that they were indeed installed, allegedly signed by the homeowner or their spouse on the date of installation. The homeowner, however, is unhappy with the windows: they are drafty; the color isn’t the same as the brochure; and goodness was this what they agreed to pay e.g. $25,000 for?! They don’t want to pay it anymore.

The bank must be the adult in this scenario, to release that second milestone payment. They very possibly could be drawn into litigation over their decision, because a few tens of thousands of dollars is just enough to justify calling a lawyer. Then the bank will have to have their own lawyers defend their own contracts in an expensive proposition over what is, to it, a small-dollar loan.

It’s not nearly this hard to generate $25,000 of balances with a credit card issuing business. You mail out the cards and people buy airplane tickets. And then the airline pays you 200 basis points off the top even before you get to originate the high-interest loan! Great business to be in and you never have to talk about a stewardess spilling someone’s drink or it raining in Hawaii that week.

Meanwhile, the window installer has their own complaints about this loan, even before it is originated. Between the day the salesman shakes hands with the customer and the bank commits to the installation, they have very little they can do to influence success. The homeowner might develop buyer’s remorse and, while they might have signed a contract, it’s just rough to compel payment for windows which don’t exist yet. Your staff will not enjoy the process, your reviews will suffer, and it’s not guaranteed that your contract will hold up: in some states, your customer might even have legal right to sever during a cooling-off period. You would prefer to accelerate delivery to avoid them cooling on the idea of windows.

But the bank is slow and has a bespoke underwriting process which requires information from you but which you cannot control, because the window installer is not the bank’s customer. They can’t call the bank up and yell at the underwriters to move faster, and they can’t debate the bank over a credit decision, where a perfectly good sale gets nixed six weeks later because the bank just isn’t feeling it. Very few of those sales will result in the buyer arranging successful alternative financing, partly for very human reasons and partly for a mechanical one: the fact of the hard pull on the credit report for the original loan origination plus non-issuance of a loan from one’s home financial institution signals to the rest of the world “Oh goodness there are probably better ex-ante risks in the economy than this one!”

No, what the window installer wants is a lending product which can be issued at scale, very predictably, in as short a timeframe as possible, by financial institutions responsive to it who ask very few followup questions, always fund milestone payments promptly, and actually want this business.

That product exists.

Modern installment loan origination as a service

Consumer credit issuance is, unless it comes directly from a manufacturer, a privilege reserved by law for regulated financial institutions. But, as we’ve established, regulated financial institutions don’t lust for this business on their own balance sheets at scale. (Recharacterizing the home improvement loan as a draw on a HELOC allows the bank to quickly get it off their balance sheet, because the HELOCs will generally be securitized. You could theoretically securitize a large pool of installment loans if you had a business process to generate them, but unless a bank specializes, they are unlikely to have core depositors simply ask for enough of these every year to justify building out the framework required to do this.)

Why is it reserved by law for financial institutions? As Bits about Money mentions often, financial institutions are a policy arm, and one thing the state requires is that Compliance make sure the financial institution is not abusing customers. The state believes that a e.g. window installer might use high-pressure sales tactics or say untrue things to a homeowner about how e.g. an interest-free financing period works, and then perhaps forget about those things when the customer complains. It believes, rationally, that financial institutions will keep extensive records of what they communicate about loans, that those records will be truthful by default, and that the financial institution will not endanger its permission to do business over a single product. Also, and this is a blunt but true observation, the state trusts white collar employees and executives at banks more than it trusts blue collar window installers.

So we need a bank involved, but that bank does not necessarily need to lend (from its own balance sheet). The bank could immediately sell a large portion of the loan, retaining perhaps 1% for form’s sake, to a private provider of capital.

But, again, it is unlikely that a bank will want to call around to hedge funds and see if there are any takers. Someone needs to have capital providers have a standing offer to snap at this product quickly.

That standing offer is variously called a forward funds flow agreement or warehouse financing. I’ve previously discussed the mechanics for Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL), and they’re the same here. Someone, typically a facilitator and not the bank itself, has brought the capital partners to the table, negotiated terms, and has prepared them to receive what they want: millions of dollars of loans, at attractive prices, with known-in-advance credit characteristics… originated by a massively scalable process, conducted partly by commission-earning sales reps bearing iPads into houses needing windows and partly by web applications and operational teams.

This machinery wasn’t originally perfected for windows. It was originally aimed mostly at solar installations, which were heavily tax-advantaged at the time. Capturing the tax credit required a sale and upfront capital outlay, and the pitch was essentially “Sign these loan docs for free money for all of us and, also, you’ll get some solar panels.” But the credits eventually expired, the addressable market for solar got more tapped, and the software and companies yearned for more originations. So, sign these documents, get windows at attractive prices.

The loan application begins with the customer verbally informing the salesman of their phone number or email address. They get given a link which swiftly brings them to a competently-designed web application. That application asks a few simple questions that are required for underwriting. The two most important ones that are not on a credit card application are “Is this your house?” and “Do you live in this house?” This is because the capital partners are much, much more confident that people will not welch on debts tied to their primary residence than that every real estate investor will be above water if 2008 happens again.

Questions about your finances are extremely pro-forma. You’ll be asked to self-state your income, but no attempt will be made to verify it. A credit report will be pulled, which satisfies the twin purposes of a) derisking the applicant pool and b) verifying, via checking for the presence of a mortgage, that you do actually own the house.

I ended up in a fraud queue at this point in the process. Story of my life. The facilitating company does not expose to the sales rep why you are in the fraud queue, but the clock is ticking, and the rep will (hypothetically) strongly prefer continuing to drink tea and chitchat rather than leaving and letting one resolve that issue asynchronously. It was resolved by a combination of automated submission of a passport photo (again, shockingly competent software by the historical standards of loan origination) and an analyst manually clicking a button in a web application.

If I were to speculate what that analyst was doing, it would be reviewing the facts: credit report says high credit score, credit report shows a mortgage, credit report does not match this address, but government-provided ID does match the asserted identity. And thus the wager: is he in his own house, or has he decided to pull a hilarious prank on a window installer and buy someone else windows with a hedge fund’s money? The analyst swiftly concluded I was probably in my own house. (Why did I end up in the fraud queue? I have a lot of weirdness, such as not being listed on the deed due to holding title through a land trust, for privacy reasons. Unfortunately, perhaps that sometimes makes it difficult for cron jobs to conclude I own the house.)

Once you’re approved for the loan, you are automatically sent loan documents for signature. This will not be compelled at the meeting, but the installer sure would appreciate you signing before they leave. Compliance has extensively briefed them on where the line is. Compliance has, in fact, extensively briefed them on many lines, and because Compliance cares more about the law than it does about paying programmers to code a login form, I was able to read their entire Compliance training series and presentations to installers.

Don’t lie. Don’t translate any loan docs from English or provide any gloss of the terms. Don’t say any of the forbidden phrases like “guaranteed approval”, “same-as-cash financing”, “interest-free financing”, etc. And definitely definitely do not touch their phone or computer during the application process.

The financial industry learned some things during the global financial crisis about aggressive salesmanship by its agents. Almost every bullet point in that 40 page PowerPoint has a stack of criminal convictions, billions of dollars of losses, or both to justify it.

What’s the actual product offered?

The salesman will first quote a scary number designed to anchor you, then present the discount available if you commit within a month. They will then say there is a sweetener if and only if you sign before they leave. Compliance is very clear that if you say that in the context of acting as an agent for a financial institution it had better not be a lie, but percentages are percentages and window companies like making deals for windows, and I would not bet against the proposition that they would offer other inducements on other days for other reasons, perhaps summing to similar numbers.

They then present financing terms. I was pleasantly surprised that this was not presented in the typical obfuscating car dealer financing four square method. The real price stays onscreen on the iPad at all times and you are presented with columns for choices: pay cash (they mean immediately deliverable value, not actually specie), 12-month deferred interest financing, 15-year fixed rate financing, and pay in milestones (e.g. 50% deposit, 50% due on installation) on a credit card.

Compliance will inform representatives that you are absolutely not supposed to use the words “same as cash” and “interest-free” to describe 12 month deferred interest financing. This salaryman is unfortunately forgetful sometimes and so I cannot quite recall what the friendly local salesman actually said while pointing to the iPad. The offer is “If you fully pay for your windows within the next 12 months, you just pay the sticker price. If it takes you longer than that, you will pay us interest, starting from the date of installation, at a rate which is materially higher than the rate we quote in the next column.”

You might think, given that sketch, that the system is trying to trick naive homeowners and surprise them on day 366 with a nasty bill. I’m slightly more sympathetic. This offer is designed to be attractive to people who can bring their own financing without making the window installation dependent on that financing. If, for example, a customer does not currently have a HELOC, but is pretty sure they can get a HELOC, the window installer is saying “Great, convince any bank to give you a HELOC, then do a draw any time in the next year and repay us, and we’ll foot the interest until then. But to be clear this window is going in irrespective of your future discussions with banks. Our capital partners do not want you to attempt to skate if your financing falls through, if you get divorced, if your tax refund is smaller than expected, etc, and you will be penalized if you attempt to turn this into a backdoor installment loan.”

But the next column is where the real action is. I was quoted 6.99% APR for equal amortizing payments over 15 years. They, naturally, express this as a monthly number, but the contract floridly and in bold print (as required by regulations) discloses e.g. total interest cost over the life of the loan, the fact there is no pre-payment penalty, etc. This is as honest as consumer lending can possibly be.

You e-sign the loan documents and then the salesman thanks you for your time and arranges for another professional to come back and redundantly measure the windows. He measured for the quote, and the quote is good, but they’ll measure again because a quarter inch matters a lot more for the physical universe than it does for the spreadsheet. Then the order goes to the factory and, a few weeks later, they install the windows. You sign an acknowledgement, and then the automated software springs back into action, starting the clock on your interest and collecting payments.

How does this pie get divvied up?

Here I am going to speculate in reliance upon publicly available data sources rather than use information which I know as a result of private commercial negotiations. Window salesmen are not the only professionals who have been to Compliance training.

In the 15-minute window between the loan being applied for and signed, software has conducted a four-way commercial negotiation between the window installer, the facilitating entity, the bank, and the capital provider. The loan contract is between the customer and the bank (again, it has to be, regs) but the capital provider is a specialist institution.

There are a few banks which specialize in doing business like this. One of them is Cross River Bank, which keeps a keen eye on trends in consumer lending.

A bank which originates a loan might charge the facilitating entity an upfront fee-for-services, collect a servicing fee from the capital providers sliced out of the APR quoted to the customer, and of course retains actual economic interest in the loan… well, OK, a few hundred dollars of the loan, so that it can tell its regulators “No, really, we are lending money! It would be calumny to describe this situation as renting out a banking license!” Indicatively, that fee for services might look something like 1% of total loan volume, and the servicing fee might be 1% of the outstanding balance annually. (Mortgage servicing fees are about 0.25% but houses cost more than windows do and so you get an economy of scale. The servicing is essentially the same amount of work: you need a 1-800 number, lawyers on standby, the capability to receive checks, etc.)

So who is the capital provider and what are they getting? It will generally be a specialist fund, like say Sunlight Financial, whose name alludes to the solar business they got started in. You might naively assume “OK, 6.99% to the consumer, 1% servicing fee to the bank, so they get 5.99% APR on the loan, right?” I doubt that is the full calculation.

One reason is that loan sounds awfully cheap: the 10 year Treasury rate is currently a hair over 4%, so why would you give a consumer 15 years fixed rate financing for 6%? Even with excellent credit quality, 2% spread doesn’t sound like enough money to make a business out of this.

But: what if, like BNPLs, you could charge someone else a bit of money? Who benefits the most from this transaction? The window installer. So charge them for it. They’re clearly willing to pay something like 2.4% of the entire transaction size already, because they will happily let you buy windows with a credit card. So that’s the floor. A BNPL provider can charge Sephora something like 6% to sell lip gloss. That might be the ceiling. So can you get them to kick in… 5%? Probably.

That moves the APR as perceived by the lender to about 7.9%. (Ask Python or Excel if you don’t believe me.) It’s a bit better than this, too, because of what will happen to the fund if interest rates fall. The value of outstanding bonds increases if rates fall, but this consumer loan might get rolled into e.g. a newly cheap HELOC if rates fall. (The free no-penalty prepayment option is a fundamental challenge in mortgage finance.) So by default this is a lose-lose situation for the lender: if rates rise the value of the loan falls, if rates fall the loan very possibly gets repaid early. But with the origination fee from the installer, if rates fall and the loan is repaid early, the return on capital over the lifetime of the loan rises sharply.

If the loan is repaid after 7 years, which is approximately the average tenure in a house in the U.S., the real rate is about 8.15%. If it’s extinguished after a year, perhaps due to rates-related refinancing, about 12%.

These numbers start to sound attractive to credit funds, particularly when you have a repeatable process for generating them at 9 figure scales with independent credit quality.

As an additional wrinkle: is Sunlight the ultimate source of capital at risk? Well, if I were Sunlight, I might think of tapping the booming private credit market: borrow at a lower rate than I earn in expectation on my portfolio, collect the spread. If I were Apollo (such a natural brand to associate with sunlight, and among the world’s largest credit funds), I might buy an insurer or figure out how to get retail investors private credit exposure to fund billions of dollars to anyone who creates a loan origination engine with demonstrable credit quality.

For much more on that side of things, you should read Money Stuff or listen to Odd Lots, which cover “private credit is the new bank lending” all the time. I’m just presenting the speculative case for how private credit turns permanent capital vehicles into windows.

Is this unsecured lending?

Compliance will tell you not to describe this as unsecured lending to the customer. I am so forgetful as to offhand comments made during sales presentations, though.

Formally, the lender does have a security interest. However, they do not want to go to the trouble of “dirtying the title” by getting a lien on the house. That can’t be done in 15 minutes. No, they only have a security interest in the window they financed.

A security interest in a car is valuable because people are quite attached to their cars and, if push comes to shove, you can repossess a car. A security interest in a house is valuable because people are quite attached to their homes and, if push comes to shove, you can foreclose on a mortgage and repossess the home. A security interest in a window is valuable because… a security interest in a window is actually not valuable.

However, by construction, the commanding majority of borrowers here have excellent credit. One factor decreasing their credit risk is that many consumers are, and this is an underwriting term of art, “judgement proof.” If you sue them for performance and a court gives you a judgement, that is worth the paper it is printed on, because they have no easily attachable assets and they might have employment in a System D fashion where garnishing their income is difficult.

A homeowner, on the other hand, always has one asset you can attach: the house, by filing a lien on it after receiving the judgement. A lien against a house is an immediately monetizable asset in the United States, because it blocks the sale of the house until it is satisfied, and there is a specialized financial ecosystem which is happy to buy that lien and then attempt collection by some combination of a) asking nicely and then in the alternative b) waiting patiently.

And so the lender’s contract is, to the extent it is concerned with credit risk, concerned with swiftly demonstrating to a court: valid contract, loan paid for windows, customer isn’t paying, issue us judgement, thank you very much, we’d like to file that judgement as a lien against coincidentally the same house. It’s only fair.

Should we be happy this Rube Goldberg machine exists?

Nice new windows are better than broken ones, and the process of buying them is now painless at an attractive financing cost. They are still expensive, but homes are expensive.

Every time anyone mentions innovation in consumer lending, the same comment is made: isn’t this just the financial crisis all over again? Aren’t we stacking up billions of dollars of low-quality loans with intermediating layers of complex products like CDO-squared? Isn’t this going to blow up?

That’s an understandable point of view. But: there is an actual underwriting process here. We replaced “You write a lie on paper, no one reads it” with a computer program that never gets bored at comparing databases. The borrower is actually reasonably good credit quality, rather than a ninja (“no income, no job”; one of the subprime lending era excesses was writing NINJA loans in quantity).

If the installer successfully leans on the origination machine to lower underwriting standards and let anyone who can fog a window buy one with a smile, then the losses are largely not in the regulated banking sector and backstoppable by taxpayers. They’re mostly to sophisticated investors in credit funds, who are being paid handsomely to take that risk. The system is also self-correcting: early defaults would cause the credit funds to tighten their risk appetites and constrain originations fairly quickly, rather than encouraging refinancing to juice origination numbers, until we were all holding (to quote Margin Call) the biggest bag of odorous excrement ever assembled in the history of capitalism.

Besides, if credit quality keeps you up at night, you should be much more concerned about bog-standard commercial real estate loans.

Want more essays in your inbox?

I write about the intersection of tech and finance, approximately biweekly. It's free.